Aproveite as férias para fazer um binge watching de video-aulas sobre a história do rock.

Participei nesses últimos meses de um curso online sobre a História do Rock, com o professor John Covach, da Universidade de Rochester.

Já tinha feito alguns antes deste, mas ainda acho difícil acompanhar porque acabo perdendo o interesse nas aulas. Talvez esse esquema de aulas online seja confortável e disponível demais para o meu nível de disciplina. Por isso optei pelo de História do Rock, para pegar ritmo (com o perdão do trocadilho). Se eu não acompanhasse esse, era para desistir mesmo.

Fiquei um tempo sem acreditar que estava diante de um professor, um senhor já, de uma respeitável universidade americana, explicando assuntos como Motown, Led Zepellin e Beatles. É uma sensação nova, essa de assistir uma aula que interessa muito. Sim, já tive aulas interessantes, mas pô, aula sobre “Sly Stone and The Rise of Funk”, “Rockabilly and The Wake of Elvis” ou “Blaxploitation Soundtracks” é novo pra mim.

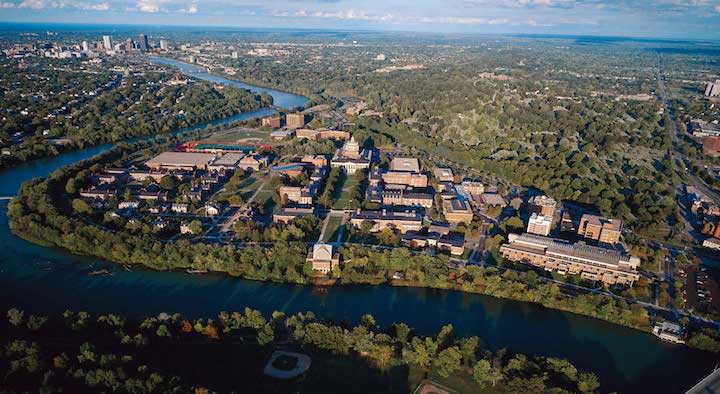

O próximo curso quero fazer in loco. Olha que Universidade linda.

E novo também para o próprio John Covach, que me enviou ontem por email um ensaio sobre a experiência de dar aula online, já que foi o primeiro a falar para o mundo pela Universidade de Rochester.

Para ler o ensaio, em inglês, basta rolar a página

Se você quiser ter um gostinho das aulas, você pode assistir muitos e muitos videos no player abaixo ou aqui. Dá para hibernar com esse material. Clique em “playlist” para ver o cardápio musical.

[mks_toggle title=”To MOOC or not to MOOC?” state=”close “]

To MOOC or Not To MOOC?

John Covach

[1] At colleges and universities across North America, online education is a topic that has generated a significant amount of

discussion in the past year or so. In many ways, the idea of online education is only the most recent version of something

that got its start in the nineteenth century: the correspondence course.(1) The development of radio and television in the

twentieth century, and then the rise of the internet over the last twenty years, has made it possible to conduct courses with

far less time lag than was present in the early days of distance learning, when lessons and assignments were carried by surface

mail. Each issue of the Chronicle of Higher Education seems to bring word of some new development or wrinkle in the rapid

development of online courses, and perhaps no topic is more controversial than MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses).(2)

While many embrace the idea that MOOCs make college-level learning available to thousands who would otherwise not have

pragmatic access to it, others worry that MOOCs threaten to put traditional college courses out of business.(3)

[2] In February 2013, the University of Rochester officially joined Coursera, one of the largest providers of MOOCs in the

world.(4) The university had considered several options regarding online education, some of these claiming to offer the

prospect of revenue generation and increased ease and flexibility for students, as well as the possibility of functioning as an

alternative to conventional classes and counting for credit. In choosing to partner with Coursera, the university chose to

place availability of knowledge above the concern for revenue: Rochester MOOCs are free, open to anyone who wants to

enroll, and do not count for college credit.(5)

[3] I was chosen to teach one of our first MOOCs and based my Coursera courses on the History of Rock class I currently

teach at the University of Rochester. Coursera recommends that regular semester courses of twelve or more weeks be broken

up into six- to eight-week courses. Accordingly, History of Rock Part 1 runs seven weeks, while History of Rock Part 2 is six

weeks in length. The courses are offered consecutively, with Part 2 immediately following Part 1; students electing the

sequence thus have a similar experience to those taking the regular semester-length course at Rochester. Coursera has found

that students tend not to stick with lectures that extend longer than about fifteen minutes; they strongly recommend

Volume 19, Number 3, September 2013

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

To MOOC or Not To MOOC?

John Covach

NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at:

http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.3/mto.13.19.3.covach.php

KEYWORDS: MOOC, online course, distance learning, Rock music, music history, Coursera

Received August 2013

1 of 6breaking up the week’s lectures into a series of shorter videos. Correspondingly, within each week of my courses there are

several lectures, each ranging from about five minutes up to fifteen minutes in length, making a total of about ninety minutes

of lecture each week. Students can either stream the videos from the Coursera site or download the videos for later viewing

offline. Coursera also suggests putting a quick quiz at the end of each of these videos, and perhaps one in the middle as well.

I decided to use these quizzes as an opportunity to review the main points of each video rather than test details from the

lecture.

[4] Consider the following video, which is drawn from Week Four of Part 1, “The Beatles and The British Invasion

(1964–66).” This video discusses the development of Beatles music from what I call a “craftsman” approach to an “artist”

approach. It is the fifth of ten videos from that week of the course.

The following quiz appears at the very end of the video, after the lecture has concluded but just before the copyright

notices.(6) The correct answers are shown with asterisks.

Which of the following statements describe the career of the Beatles and rock authenticity as

discussed in the video (mark all that apply)?

*The idea of authenticity in rock music means that artists write their own songs and play their own

instruments on recordings. The songs are thought to represent “who you are.”

*The Beatles shifted from an approach that reflected a “craft” in making their music to one increasingly

dominated by the “artist” model.

The Beatles rejected most of Bob Dylan’s work, finding it pretentious and vague.

As you can see, all three responses deal with the most general points made in the video—authenticity, craft to art, and

Dylan’s influence. If a student does not answer the question correctly, s/he can try again until the correct answer is submitted

or even skip the quiz altogether. These quizzes do not figure into the grade and thus serve only as study aides.

[5] Each of the videos that make up both of the courses (sixty-two in Part 1, fifty-four in Part 2) was recorded once and they

were done in sequence. I stopped a few times to redo sections, but mostly the lectures were delivered as one would in class—

straight through and without stopping. You may notice that I seem to be looking off camera to my left at certain points; I

have a music stand just out of the shot containing my lecture notes. As I soon found, the notes had to be much more

detailed than the ones I would normally use in class because the video format is far less forgiving of inaccurate data. In class

you can admit you’re not sure of a fact and maybe have a student look it up while you lecture; but in the videos it has to be

right the first time. From this perspective, the lectures are more like a textbook than a typical in-class teaching presentation.

[6] The grades for each course are based on quizzes taken at two-week intervals. These quizzes are automated, with all

grading done by the Coursera software and with students able to take each exam up to three times (the highest grade is the

one that counts). Students who earn 70% or more of the available points receive a Statement of Accomplishment; those who

score 90% or more receive a Statement with distinction.(8) There is a discussion forum for the course; each week I post three

questions and students will often pose their own as well. Participation on the forum, however, does not figure into the grade.

Though students may receive Statements of Accomplishment, no student earns college credit from Coursera or the

University of Rochester.

[7] History of Rock Parts 1 and 2 were offered over the summer of 2013 with a combined enrollment of over 70,000.(9) Of

those enrolled, approximately 44,000 (63%) participated actively. Video views surpassed one million and downloads topped

600,000 . Most students seem to have watched the videos without taking the exams, or maybe only watched the videos that

interested them. Less than 10% of the students participated in the discussion forums, though even that level of engagement

created a tremendous amount of traffic on the hundreds of threads. At the conclusion of Part 1 we awarded 4747 Statements

of Accomplishment, 1460 of those with distinction; for Part 2 we awarded 3545 Statements, 2978 with distinction.. These

numbers are roughly consistent with other Coursera courses.

2 of 6

[8] Preparing and teaching this two-course sequence was a lot of work. Simply filming the videos took about 40 hours overall

(three hours for each week of the course), while preparing the notes took another 52 hours (four hours for each week).

Creating the individual quizzes for each video and the exams required 40 additional hours, with another 26 hours used to

monitor the discussion forum and take care of other kinds of online course details. That brings the total time to prepare the

course to approximately 158 hours. The video editing and photo research was done by University of Rochester staff, as was a

significant portion of the interfacing with Coursera and the course software.(10) These combined tasks add perhaps as much

as 300 hours to the total time required to mount a thirteen-week MOOC. Of course, once this work is done, subsequent

sections of the course require only a few hours per week of maintenance; the course becomes a bit like a machine that can

run almost on its own (or so one hopes).

[9] While I would not recommend this workload for any untenured faculty member, I do not hesitate to admit that teaching

this MOOC was one of the most gratifying experiences in my teaching career.(11) One of the things that made this

experience so positive for me was the ownership the students took in the course. From the opening moments, the students

began answering each other’s questions and solving problems that arose. For instance, we could not play or post any music in

the course because of copyright restrictions. I worried how this was going to work out once I started mentioning songs in

the lectures. But almost immediately students began posting playlists in the discussion forum, employing various servers to

get all the music posted (including a server in Russia). One fantastic student began a Facebook page, where students engaged

in discussion, shared playlists and video links, and created a community dedicated to the course content with a seriousness of

purpose that would gladden the heart of any teacher. It was clear that the course mattered a lot to these students and they

were working very hard at it.(12)

[10] There were some surprises regarding the geographic and demographic data on the students.(13) About 68% of the

students resided outside of the United States.(14) About 33% of the students were between the ages of 22 and 29, with

another 16% in the 30–39 age range. 35% of the students had already earned a bachelor’s degree; 26% held a master’s and

5% held a doctorate. If those percentages reflect the active students, that would mean that more than half the students are

not college undergraduates, and most are not Americans. For those concerned that MOOCs will replace undergraduate

college courses in North America, these figures offer some consolation. In terms of gender, 53% of the students were male

and 47% female.

[11]There are certainly significant pedagogical limitations to the MOOC format, the most obvious being the lack of real-time

interaction with students. The format of the testing also makes in very difficult to employ anything other than multiplechoice or fill-in-the-blanks questions.(15) It is possible to have students write papers, and Coursera reports good results with

peer-graded papers (the students grade one another). Ultimately it is the sheer number of students that makes it very difficult

to replace the traditional college classroom experience with a MOOC, at least when it comes to humanities courses. Add to

this that Coursera is what one might call a “free culture,” meaning that the course itself should be as cost-free as possible.

This makes requiring a textbook that students must purchase an unpractical option.

[12] My experience has caused me to stop thinking of the MOOC as an alternative to the traditional college course. It is

rather something like a very organized series of public lectures based on the structure of a college course. MOOCs are most

valuable as a way of bringing the wealth of knowledge we produce and preserve in the academy to the broadest possible

public—something, it must be admitted, we probably do not do enough. I use my MOOC video lectures in my regular

course at Rochester now; I assign these lectures to students and this frees up class time to focus on particular pieces and

discussions that we might not otherwise have gotten to.(16) In fact, I can imagine that a “MOOC-plus” approach—a scheme

whereby a MOOC (or part of one) would be employed as part of a regular, credit-earning course—might well be a part of

awarding college credit more broadly in the future.(17)

[13] The future of online education is rapidly developing; what it may look like even a year from now is uncertain. It is clear,

however, that online education is not going away, at least not in the United States. Last December, thirteen-year olds all

across the country got iPads or some other tablet device as holiday gifts. These young people may not be in our classrooms

yet, but in a few years they will be. And when they arrive, they will prefer to work from their handheld device (rather than a

3 of 6textbook) and they will be comfortable absorbing content online. They will be veterans of Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr,

Instragram, and whatever else pops up between now and then. They may even hope that college is a series of TED lectures.

It’s up to us to be ready for them: love it or hate it, this technology is coming. We are probably wise to own it before it owns

us.

John Covach

University of Rochester

Department of Music

PO Box 270052

Rochester, NY 14627-0052

[email protected]

Works Cited

Berg, Gary A. 2005. “History of Correspondence Instruction.” In Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, Volume 2, ed. Caroline

Howard et al., 1006–11.

Kolowich, Steve. 2013a. “As MOOC Debate Simmers at San Jose State, American U. Calls a Halt.” The Chronicle of Higher

Education, May 9. http://chronicle.com/article/As-MOOC-Debate-Simmers-at-San/139147/.

—————. 2013b. “The Minds Behind the MOOCs.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, August 14.

http://chronicle.com/article/The-Professors-Behind-the-MOOC/137905/#id=overview.

—————. 2013c. “Why Professors at San Jose State Won’t Use a Harvard Professor’s MOOC.” The Chronicle of Higher

Education, August 14. http://chronicle.com/article/Why-Professors-at-San-Jose/138941/.

Footnotes

1. For a history of the correspondence course, see Berg 2005.

Return to text

2. For an introduction to MOOCs, see “What You Need To Know About MOOCs” in The Chronicle of Higher Education,

http://chronicle.com/article/What-You-Need-to-Know-About/133475/.

Return to text

3. There are, of course, many shades of opinion between these two extremes. Kolowich 2013a gives some idea of how

passionate these debates can become.

Return to text

4. For more about Coursera, see the early notice of this for-profit company’s activities at http://www.marketwire.com/pressrelease/coursera-secures-16m-from-kleiner-perkins-caufield-byers-new-enterprise-associates-bring-1645322.htm.

Return to text

5. This is also true of most of the universities currently partnering with Coursera. The issue of whether or not such courses

can or will count for college credit is a lively one in academe. It is worth bearing in mind that MOOCs are only one kind of

online course. Online courses with smaller enrollments can and have been used to substitute for regular college courses, as

did one I taught on rock music at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill over ten years ago. Many schools have

used online education effectively, including the University of Rochester, which offers non-MOOC courses in several of its

professional schools.

4 of 6Return to text

6. The quiz formatting is part of the Coursera software and cannot be replicated here. It is worth noting that students who

download the videos for viewing later also cannot see these quizzes.

Return to text

7. Coursera subtitles all lectures in English, while also incorporating a function that slows the video down or speeds it up.

The slow-down function, in conjunction with the subtitles, is often used by students for whom English not the primary

language; the speed-up function can be used to review lectures before exams.

Return to text

8. Instructors are able to adjust the numbers of times an exam can be taken, when the exams are due, and how much credit is

subtracted for late submissions, as well as many other variables. They may also decide what percentage qualifies a student for

the certificates.

Return to text

9. Almost 43,000 enrolled in Part 1 with about 28,000 in Part 2. Some of those in Part 2 had been in Part 1, but many in Part

2 were new to the course.

Return to text

10. The videos were edited by Will Graver, who was also in charge of the video shoots. Will had my notes and could thus

insert those points into the video. The pictures were researched by Eric Fredericksen, who also took care of much of the

interaction with Coursera and with technical online aspects of the course.

Return to text

11. The remarks that follow may be compared with those of others who have recently developed and taught MOOCs; see

Kolowich 2013b.

Return to text

12. In one post a student explained that his method was to watch each video and stop every time I mentioned a song and

listen to it. I probably mention 100 or so songs a week!

Return to text

13. The following remarks are based on a voluntary survey that students of Part 1 were asked to complete (almost 8000

responses). They are therefore not scientific and may only provide a rough profile of the dimensions discussed here.

Return to text

14. The three highest represented countries outside the US were Brazil, followed by Spain and India. The forum had

discussion rooms for non-English speakers, and these included Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, and Chinese study groups,

among others.

Return to text

15. I often employ approaches that combine multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank to make the questions demanding without

being tricky.

Return to text

16. We have made the videos for both parts of the History of Rock available on the University of Rochester Institute for

Popular Music website (http://www.rochester.edu/popmusic/courses/rock-history-pt-1.html). Colleagues are welcome to

use them freely.

Return to text

17. This approach has been referred to as the “blended approach” and was part of a dispute at San Jose State University

5 of 6regarding the use of MOOC videos from edX, an organization formed by Harvard and MIT (see Kolowich 2013a and

2013c). Using MOOC videos in a blended course that enrolls less than 100 students is not a MOOC, and one can see how

categories of online education and resources can become confused and the debate become fractured.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO

may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly

research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from

the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the

medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was

authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its

entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO,

who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may

be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

6 of 6

[/mks_toggle]